Notes from Intro to Git talk at NREL

11 March 2018

SUMMARY

Use Git. Here’s how: git-guide.

Get a git cheat sheet here.

WHAT IS VERSION CONTROL

Version control, also known as revision control or source control, is the management of revisions to documents, code, or other digital things. Essentially, version control systems establish a timeline of revisions.

Additionally, the following information for a revision is stored:

- The contents

- The reason

- A timestamp

- The author

- A unique ID

This documented history of all revisions can be opened for review at any time in the future.

Version control systems can be used for any file type, but are generally most useful for text files since particular changes can be tracked. A major limitation to this idea is in state-saving files for some programs which use a dictionary-like file structure. For example, Xcode projects and Jupyter Notebooks have file structures in which some line ordering can change while maintaining the value of the contents. Here, version control weights inconsequential changes equal to those that matter.

WHY USE VERSION CONTROL

The benefits of version control for a team of one are straightforward, but the benefits become exceedingly more important as team size grows.

COMMUNICATION

Other members of the team can understand updates to a project without the need to talk to the author directly.

DOCUMENTATION

The history of revisions serves as a base level of documentation for all changes. If used appropriately, it can directly serve as a change log.

COLLABORATION

In decentralized systems like Git, multiple people can easily work on the same file concurrently.

CONTINUOUS INTEGRATION AND TESTING

Automated testing infrastructure can be hooked into the version control system to serve as a final gatekeeper.

SAVE YOUR WEEKEND

Without version control, discovering a bug on Friday at 2 pm is a great way to guarantee working through the weekend. Maintaining a history of revisions means you can always step back in time and isolate the problem quickly.

GIT

Some options for version control are

- Git

- cvs

- Mercurial

- Apache Subversion (svn)

Of these, Git is the most popular and has significant infrastructure in the software development community, and its the primary version control system in use at NREL.

Git is a decentralized system meaning that every repository stands alone and can be cloned to create another repository. Merging revisions is very simple and a common part of the Git workflow so one file can be modified simultaneously without too much headache. This is an improvement over older centralized version control systems where each file is checked out and locked for editing by a single user. Git works by storing subsequent revisions of files in a series. This tree object operates similar to a blockchain] in that it is a distributed ledger and a chain of blocks. And there is a lot of hashing.

What goes on under the hood is interesting but quite complicated, so that could be added here in the future. References are available here, here, and here.

TERMINOLOGY

Stage – the set of changes that will consist of the next commit (actually stored in .git/index)

Commit – a single recorded revision

Branch – a particular time series of commits

Remote – a version of the project the exists somewhere outside of your working project

Upstream – the branch on a remote repository that a local branch is “tracking”

Fork – a copy of a repository

COMMANDS

The syntax for all commands is

git <command>

and the help page can be seen with

git <command> --help

# for example

git add --help

The commands below are linked to their respective git-scm documentation pages.

GIT INIT

Creates the .git directory which contains all of the necessary files needed by Git. This command must be run before using a repository.

GIT STATUS

List the current state of the staging area and differences between local and remote.

GIT ADD

Add files to the stage.

GIT COMMIT

Record changes to the repository (consists of the message, staged changes, parent commit, and tree hash).

GIT BRANCH

Manage branches in a local repository.

| Functionality | Command |

|---|---|

| List | git branch -a |

| Create | git branch |

| Delete | git branch -d |

GIT REMOTE

Manage the connections from a local repository to a remote repository.

| Functionality | Command |

|---|---|

| List | git remote -v |

| Add | git remote add |

| Remove | git remote rm |

GIT FETCH

Get the latest revisions from a remote, but do not apply the changes locally.

GIT CLONE

Create a local copy of a remote repository.

GIT PULL

Incorporate the revisions on a remote repository into a local repository.

GIT PUSH

Incorporate the revisions on a local repository into a remote repository.

GIT MERGE

Join multiple branches.

GIT CHECKOUT

Switch to another commit or branch, or restore working tree files.

BRANCH AND MERGE

Branching and merging are central concepts to Git and a Git Flow model has been generally adopted in this regard. A really good writeup on Git Flow and the source for the following images are here.

Though a branch may have any name, Git Flow calls for a particular naming scheme

main is the primary branch. It is updated less frequently than others

and should always remain stable. develop is the working branch. It is

updated when features are thought to be complete but is not always stable.

feature/ are dedicated to a single particular feature. These branches

are not typically stable, but should be merged into develop upon

reaching a stable point. hotfix/ are critical bug fixes. These

branches should maintain a very small scope and are merged into both

main and develop when complete. The graph below highlights the

flow from main to develop and feature/.

CREATING A BRANCH

Create a branch with the command

git branch <branch-name> <start-point>

where

branch-nameis something likefeature/add_plottingorhotfix/divide_by_zerostart-pointis a commit hash or a branch name

Note – branch names are simply aliases to a particular commit, and commits can exist in a repository without being attached to a branch.

This command creates but does not checkout the branch. To create and checkout a branch, use the command

git checkout -b <branch-name> <start-point>

MERGING A BRANCH

When a branch is stable or finished, merge it into another branch with the command

git merge <donor> <receiver>

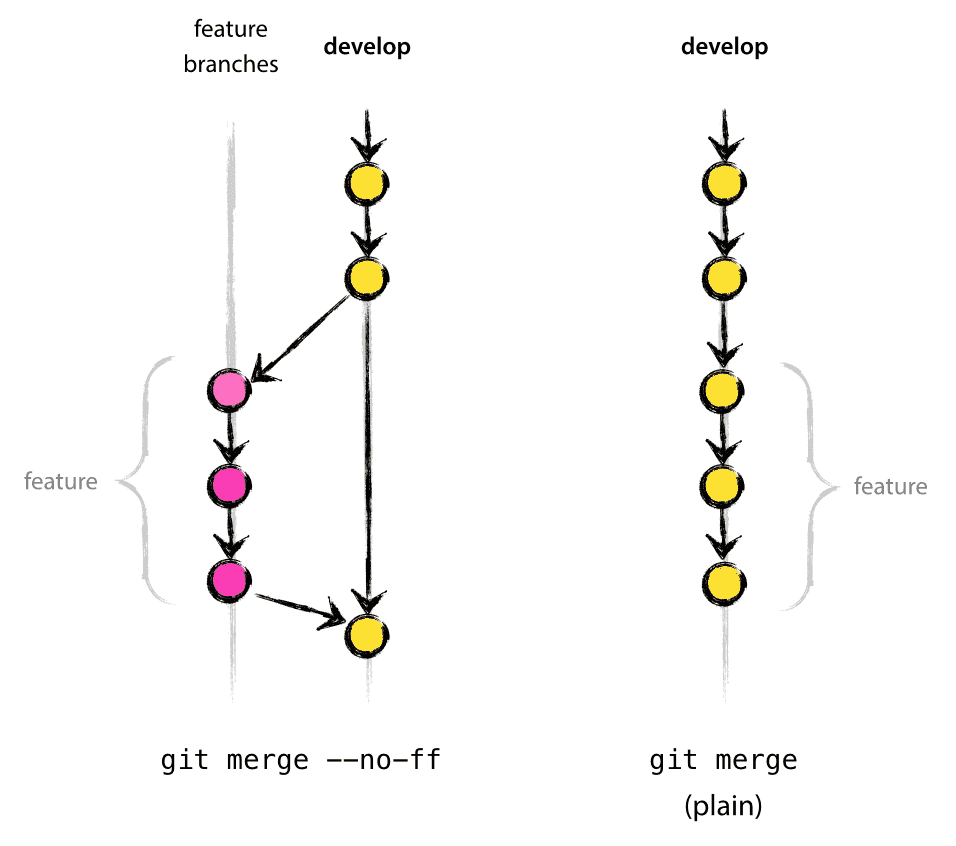

Git tries to merge branches by adding the additional commits

from donor on top of the commits in receiver, if possible,

in what is called a fast-forward. This simply adds the news

commits on top of the old commits and updates the hash where

the branch name points. If this is not possible, such as when

revisions have occurred simultaneously, then an additional merge

commit is created indicating that a branch was merged.

Note - adding the flag –no-ff forces Git to create a merge commit

which can be desirable since it keeps a history of all branch merges.

This graph below indicates merging with and without a ”fast-forward”.

DELETING A BRANCH

After merging a branch, it is typically no longer needed. When this is the case, you can delete a branch from the local repository with

git branch -d <branch-name>

If the branch was not directly merged in (possibly included as a

pull request to the main repository instead), and you’re sure you

want to delete it, use -D instead. Of course, you cannot be

currently on the branch that you are deleting. Also, delete

the remote branch with

git push -d <remote-name> <branch-name>

REMOTES

Each remote has a name or alias that is used in Git commands.

If a repository is cloned from a server, the default remote

name is origin and it is set to point to the location where

it was cloned. However, additional remotes can be added at any

time. The name origin is meaningful to Git as it is used as

the default remote for most commands when one is not supplied

or not inferred. Therefore, be sure to know where a repository’s

remote is pointing before interacting with it.

A local repository can have multiple remotes. It is common to have one pointing to the developer’s fork of a repository with the name origin and another pointing to the main repository with the upstream.

HOSTING SERVICES

The repository hosting ecosystem around Git is comprehensive with free and paid options for varying needs. Typically, free-tier services exist for open source software. Some of the more popular hosting services are

- GitHub

- SourceForge

- BitBucket

NREL primarily uses GitHub but in a variety of ways…

GITHUB.COM

The various teams and researchers have accounts which host our many public open source projects, like FLORIS on the WISDEM account. Free-tier users can have an unlimited number of repositories and files are limited to 100 MB, but all repositories are public.

GITHUB.COM/NREL

An account under the NREL name also exists and is managed by ITS. NREL staff can be added to a GitHub team which has access to this account by emailing Mic Stremel Mic.Stremel@nrel.gov. The repositories on this account are hosted on GitHub servers. One benefit of this is the access to private repositories which can be shared with individual external collaborators. Public repositories can also be added to this account.

GITHUB.NREL.GOV

This is an instance of the GitHub service managed by NREL staff and running on NREL servers. All researchers have access to this service with your ITS username and password. The repositories here are behind the NREL firewall so you must be on the NREL VPN to access any of the data including using any of the git commands from the command line.

ANYWHERE!

Fun fact: You can host a remote in any file system accessible to your computer such as another directory on your computer, an external drive, a network drive, or a server like peregrine.

CLIENTS

Git clients are programs that abstract the commands into a more friendly form, typically a GUI. These can be very helpful but offer a subset of all of the commands available in the Git command line interface.

Here are some good clients

- Git Kraken

- GitHub Desktop

- Tower

- Sublime Merge

GIT CONFIG

A proper git configuration can be a huge help in using Git on the command line.

On a linux system, you do this by creating a file at ~/.gitconfig. A starter

git config is shown below.

[user]

name = You R Name

email = you.r.email@nrel.gov

[alias]

# Command # Usage

st = status # git st

co = checkout # git co <branch name>

last = log -1 HEAD # git last

bra = branch -avv # git bra

rmv = remote -v # git rmv

f = fetch --all # git f

unstage = reset HEAD # git unstage <file>

ga = log --graph --abbrev-commit --decorate --format=format:'%C(bold blue)%h%C(reset) - %C(bold green)(%ar)%C(reset) %C(white)%s%C(reset) %C(white)- %an%C(reset)%C(bold yellow)%d%C(reset)' --all # git ga

gb = log --graph --abbrev-commit --decorate --format=format:'%C(bold blue)%h%C(reset) - %C(bold green)(%ar)%C(reset) %C(white)%s%C(reset) %C(white)- %an%C(reset)%C(bold yellow)%d%C(reset)' # git gb

# I've never actually used these

br = branch # git br

ci = commit # git ci